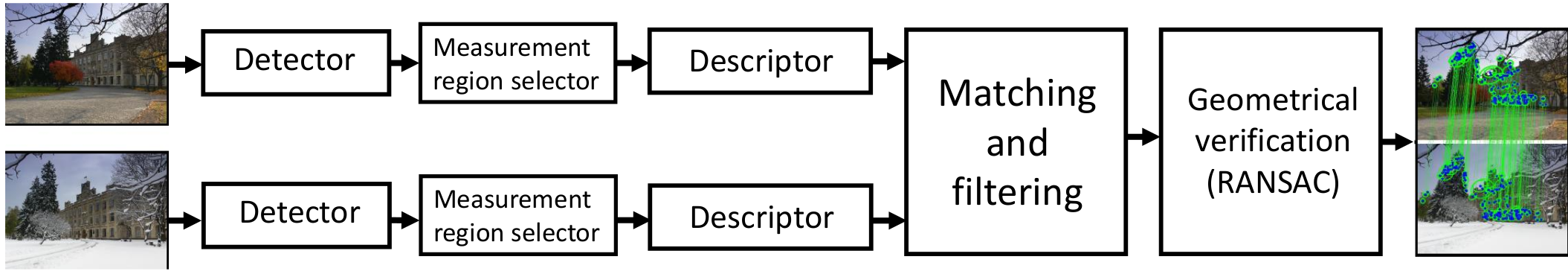

Delving deeper into WxBS algorithm steps

The wide baseline stereo problem is commonly addressed by a family of algorithms, the general structure of which is shown in Figure above. We will be referring to it as the WxBS pipeline or the WxBS algorithm. Let us describe it in more detail and discuss the reasoning behind each block.

- A set of the local features (Also known as keypoints, local regions, distinguished regions, salient regions, salient points, etc.) is detected in each image independently. In automated systems the local features are usually low level structures like corners, blobs and so on. However, they can also be more high level semantic structures, as we used in the example in intro: “a long staircase on the left side”, “the top of the lampost” and so on. An important detail is that detection is typically done in each image separately. Why is it the case? If the task is to match only a single image pair, that would be an unnecessary restriction. It is even benefitial to process the images jointly, as a human would do, by placing both images side-by-side and looking at them back and forth. However, the wide baseline stereo task rarely arises by itself, more often it is only a part of a bigger system, e.g. visual localization or 3D recontruction from the collection of images. Therefore, one needs to match an image to not the one, but multiple other images. That is why it is benefitial to perform feature extraction only once per image and then load the stored results. Moreover, independent feature extraction is a task which is easy to parallelize and that is typically done in most of libraries and frameworks for the WxBS. One could be wondering if the local feature detection process is necessary at all? Indeed, it is possible to avoid feature detection and consider all the pixels as “detections”. The problem with such approach is the high computational and memory complexity – even a small 800x600 image contains half a million pixels, which need to be matched to half a million pixels in another image.

- A region around the local feature to be described is selected. If one considers a keypoint to be literally a point, it is impractical to distinguish between them based only on coordinates and, maybe, the single RGB value of the pixel. On the other extreme, part of the image, which really far from the current keypoint helps little to nothing in terms of finding a correspondence. Thus, a reasonable trade-off needs to be made. Keypoint therefore can be think of as the “reference point of the distinguished region”, e.g. a center of the blob. It worth mention that some detectors return a region by default, so this step is omitted, or, to be precise, included into step 1 “local features detection”. However, it is useful to have it discussed separately .

- A patch around each local feature is described with a local feature descriptor, i.e. converted to a compact format. Such procedure also should be robust to changes in acquisition conditions so that descriptors related to the same 3D points are similar and dissimilar otherwise. The local feature descriptors are then used for the efficient generation of tentative correspondences. Could one skip this stage? Yes, but as with the local feature detection, the skipping is not desirable from a computational point of view – the benefits are discussed in the next stage – matching. Local feature detection, measurement region selection and description together convert an image into a sparse representation, which is suitable for the correspondence search. Such representation is more robust to the acquisition conditions and can be further indexed if used for image retrieval.

- Tentative correspondences between detected features are established and then filtered. The simplest and common way to generate tentative correspondences is to perform a nearest neighbor search in the descriptor space. The commonly used descriptors are the binary or float point vectors, which allows to employ various algorithms for approximate nearest neighbor search and trade a small amount of accuracy for orders of magnitude speed-up. Such correspondences need to be filtered, that is why the are called “tentative” or “putative” – a significant percantage of them is incorrect. There are many reasons for that – imprerfection of the local feature detector, descriptor, matching process and simply the fact that some parts of the scene are visible only on one image, but not another.

- The geometric relationship between the two images is recovered, which is the final goal of the whole process. In addition, the tentative correspondences, which are not consistent with the found geometry, are called outliers and are discarded. The most common way of robust model estimation in the presense of outliers is called RANSAC – random sample consensus. There are other methods as well, e.g. re-weighted least squares, but RANSAC predominantely used in practice.

Everything you (didn’t) want to know about image matching